What follows is a real example of the power of forward-looking OSINT monitoring: in this case it helped to save one global bank the tidy sum of $100mn.

- In early August 2014 a leading Portuguese bank collapsed, leaving shareholders, depositors, counterparties and creditors nursing their wounds. Banco Espirito Santo was subsequently rescued by the State and broken up into a “good bank” and a “bad bank”. The shareholders lost everything.

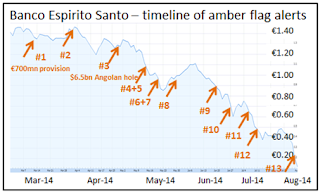

- Using our “early warning” system, clients were first alerted to problems during the fourth quarter of 2013, when the Portuguese press carried stories of a major rift between the two principal figures of the Espirito Santo family that controlled the bank: two cousins, the CEO and the head of the investment banking arm.

In March

2014 we published our first “amber

flag” citing an unexpected provision of €700 million being made by the

bank’s direct parent company: this was a massive provision relative to the size

of the bank, and little explanation was given as to the need for the provision.

Ten days later, adding insult to injury, the bank postponed its AGM for the

third time – with no explanation.

As part of the overall early

warning system, I actively monitor some 300

investigative journalists world-wide. Having built an initial search

algorithm that included the bank’s name and its various acronyms, plus a

plethora of key words in Portuguese, Spanish, French and English, an alert was

triggered by an article in Portuguese by a blogger from Luanda, Angola. I don’t

know Rafael Marques de Morais (the

human rights activist and blogger), but it was fairly easy to verify the

quality of his content: simply put, he gets beaten up and shoved into jail by

the Angolan authorities on a fairly regular basis – so clearly some of his

words must hit a chord.

On April

30th 2014, just a month after news of

the massive provision being made by the bank’s parent, Mr Marques wrote in is

MakaAngola blog that the Angolan subsidiary of Banco Espirito Santo (BES

Angola) had a $6.5 billion dollar hole in its balance

sheet reprinting the story in

English the following day. If this was true, the Angolan

subsidiary was bust and the Portuguese parent would need to write-off the value

of its capital invested in the subsidiary; that would equate to the entirety of

the bank’s CET1 cushion and mean that the parent bank would need a capital

increase. The size of the supposed hole ($5bn of toxic loans and $1.5bn of

unpaid interest) raised the question as to just how much BES Angola had in

deposits, and data from the Central Bank of Angola’s web-site suggested that it

had but $2 billion of deposits. So just how had it managed to lend out $5

billion with just $2 billion of deposits? If the story was true, the most

likely answer was that the Portuguese parent had passed $3 billion down to the

Angola business in the shape of interbank loans. The Angolan bank had then

"lent" these funds, without any collateral or guarantee, to various

members of the Angolan elite: all $5bn of it!

One might imagine that this

would be a big story in the Portuguese press, for if the lending gap had been

covered by Banco Espirito Santo (parent) then then resulting $3bn hole in the

parent's balance sheet could mean that it was also bust. Needless to say there

was not a mention of the issue in the Portuguese press; indeed the story only emerged after

the bank had collapsed four month later on July 29th, with no less a source

than the New York Times discussing the Angolan issue. So as of early May 2014,

with the news of a potential black-hole out there on the internet, the market

value of the bank was still around the €5bn level.

Subsequent to the MakaAngola

article matters at the bank deteriorated, but in mid-May, just two weeks after

the above article was published, the bank made a capital increase for €1bn,

which was fully underwritten by a banking syndicate that included many of the

leading global names in investment banking. For anyone following the amber

flags this would not have been a surprise. In parallel to this announcement, on

the 15th May the bank stated that its long-term co-owner, Credit Agricole,

would not be taking up their rights, and furthermore were terminating their shareholder agreement.

That didn't seem to worry anyone either.

One week later a formal audit

of the bank ordered by the Portuguese regulator “uncovered significant

irregularities” at the bank’s Espirito Santo International affiliate, and from

then on things got worse. Yet despite the falling share price and poor news, a

very well-known US global investment bank decided to help lend $800mn to one of

the group’s holding companies. The message to the market was clear: "if

that bank thinks that this is a good bet, then it is". Soon after that

reprieve the Portuguese regulator threw out the new management team that had

been proposed by the family, and a few weeks later, on the back of yet further

negative surprises, the Bank of Portugal stepped in and nationalised the bank. The shareholders lost everything.

Yet

between March and August we had posted thirteen different amber flag warnings regarding the

bank. The search algorithms were not massively complex, they were just in four

or five languages and capable of searching the periphery rather than just the

mainstream news. Yet neither the underwriters of the rights issue, nor the

lenders of $800mn to the parent company seem to have bothered making the most

simple of checks. The truth of the matter is that in the case

of Banco Espirito Santo everything was in plain sight, but no-one wanted to

notice. The one bank that did take notice pulled $100mn loan just days

before the final dénouement: it had been following the amber flags: おめでとう.

You composed this post cautiously which is beneficial for us. I got some different kind of information from your article and I will suggest reading this article who need this info. Thanks for share it.Loteria nacional dominicana

ReplyDelete